SWIMMING TO CHINA

| EAST BAY EXPRESS |

AUGUST

25 - 31, 2000

|

BY KRISTIANNA BERTELSEN

A JOYFUL TIME

Paintings by Zhang Xiaotao, through September 1, at the Pacific Bridge

Gallery, Oakland.

By Kristianna Bertelsen

In one party game, there is a psychological

test that poses this question: "You’re alone, you’re in the

middle of the ocean, and you’re naked. How do you feel?" After all

have responded, they are debriefed and told that their answers reflect

their emotional attitudes toward sex. Thus, someone who answered "elated

and free" is sexually uninhibited, and anyone who answered "scared" will

probably run and hide at the suggestion of Spin the Bottle.

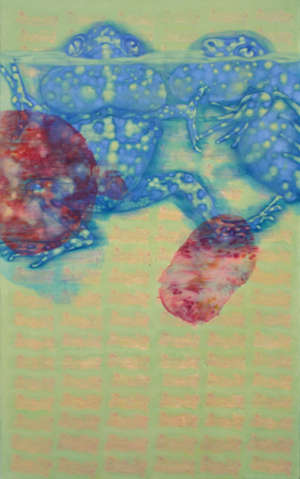

Walking into Zhang Xiaotao’s "A Joyful Time," where huge oil and watercolor paintings invite viewers into a bright underwater world of copulating frogs and intertwined human forms, the reaction "elated and free" comes back to mind. Amphibious creatures float unencumbered in washes of blue, green, and orange paint, their outlines making whimsical, eye-pleasing shapes. So it is with great surprise that one learns of the artist’s background—that he nearly drowned as a child and is afraid of water, and that he comes from a country whose reproductive policies are heavy-handed and punitive.

This is Zhang’s first exhibit in the United States, accompanying a month-long residency at the Pacific Bridge Gallery, which last spring garnered attention for its controversial exhibition of Ho Chi Minh portraits. Zhang, who is 29, has a degree in oil painting and teaches it at Southwest Jiaotong University in Chengdu.

Among Chinese artists, oil painting has caught on as a fashionable and innovative expression of Western energy. In the hands of a skillful painter like Zhang, it reflects the character of an ancient culture while embracing modern themes and colors. Fish, snakes, human faces, beer mugs, condoms—these repeating elements appear in intricate layers of paint that defy opacity. The creatures’ hues are often the blues and greens of the traditional Chinese pottery and carvings that abound in jade markets, but placed in front of or behind the animals’ outlines are shapes and symbols that would challenge, if not startle, any unsuspecting market habitué.

In more than one painting, a pair of frogs hug blissfully, doggie-style. They are free-falling, not anchored to anything except each other—getting ready, perhaps, for their parachutes to open. On one canvas, they look skyward against a backdrop of floating clouds. On another surface, their background is a motif of human couplings taken from an ancient Chinese "pillow book" of how-to positions for adults.

The repetitiveness of these pillow-book images evokes pop art. But where Andy Warhol used a checkerboard of soup cans or Marilyn’s head, here the repeated element is always erotic: trios and couples in sexual play, sprinkled lightly across the backdrop. They make the canvas, from a distance, look like a textile, like a bedsheet.

While pop artists of the ’50s and ’60s were paying homage to postwar consumerism and icons of mass-production, China was still in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. But here Zhang turns to his artistic predecessors and, as if making up for lost time, incorporates their method. Even the vibrant sheen that some of his paintings seem to give off is reminiscent of silkscreening, a mass-production technique that Warhol adopted in the early ’60s.

Some of the largest works, at the back of the gallery, are also the most provocative. In dark gray-green hazes float huge, rubbery shapes. They are transparent sheaths with reservoir tips, and faces peer from behind, or inside. Tiny bubbles are suspended within the wrinkled tubes, and here and there a splattered dollop of red paint contrasts with the green. The faces glisten as if behind a windowpane, and their wide-eyed constraint elicits sadness.

Everywhere in Zhang’s work one finds splotches of the red paint. It appears to be mixed with something that won’t quite blend with it, and the effect is that of a potato stamp made from a bumpy, many-eyed spud. In the context of sex and birth, though, these bubbles and deep-red blotches are semen and blood. They are the repeating threads of humanity: liquids that transmit life,

inheritance, and the most essential fluids of ancestry—containing not only DNA, but also the ways in which we (both animals and humans) need each other and hurt each other. In their aqueous environment, the drops, smears, and splotches also remind one of amoebas seen under a microscope, like beads of a primordial sea.

Throughout

the gallery, the sensation of water is hard to shake. The oil paint itself

has a liquid quality—it has been thinned enough to resemble watercolor

from a short distance —and layered images often appear soaked, suspended,

or dripped on. Zhang’s frequently recurring dreams about drowning

presumably account for all the water imagery in his work; his preoccupation

stems from two swimming accidents when he was seven years old: one happened

at the shore of the powerful Yangtze River, where he was playing with

his companions. His brother’s friend had pulled him into the current,

teasingly, but soon lost control and had to swim ashore. Zhang remained

out in the water and was almost dead before an adult who could brave the

current came to his rescue. That tentative, struggling moment between

life and death informs the artist’s work expansively. In an essay

that accompanies the exhibit, he writes, "Green mountain and clear water

were beautiful and perplexing with green treacherous light sparkling,"

and he recalls "hopelessness and despair, being on the verge of death,

the efforts to catch anything, and the attempt to rush upward." His watery

paint-strokes summon additional, related junctures of mortal existence:

the point between conception and life, the limbo between death and afterlife,

the suspension of time during coital climax.

Throughout

the gallery, the sensation of water is hard to shake. The oil paint itself

has a liquid quality—it has been thinned enough to resemble watercolor

from a short distance —and layered images often appear soaked, suspended,

or dripped on. Zhang’s frequently recurring dreams about drowning

presumably account for all the water imagery in his work; his preoccupation

stems from two swimming accidents when he was seven years old: one happened

at the shore of the powerful Yangtze River, where he was playing with

his companions. His brother’s friend had pulled him into the current,

teasingly, but soon lost control and had to swim ashore. Zhang remained

out in the water and was almost dead before an adult who could brave the

current came to his rescue. That tentative, struggling moment between

life and death informs the artist’s work expansively. In an essay

that accompanies the exhibit, he writes, "Green mountain and clear water

were beautiful and perplexing with green treacherous light sparkling,"

and he recalls "hopelessness and despair, being on the verge of death,

the efforts to catch anything, and the attempt to rush upward." His watery

paint-strokes summon additional, related junctures of mortal existence:

the point between conception and life, the limbo between death and afterlife,

the suspension of time during coital climax.

One painting features the open mouth of a crocodile with lightly sketched people walking, swimming, and floating in and out of its jaws. The paint bleeds a pink wash over the traffic entering and exiting the gates of a pastel inferno. Tiny sharp teeth, like icicles and stalagmites, frame the passageway.

Three smaller paintings, in watercolor and tea on ragged notebook paper, show more of these ungrounded human forms floating above intermingled ocean-floor organisms. Even these fantastical creatures—some with squid-like heads, flippered bodies, and eel-like tails—are paired amorously, as though they fit together most naturally that way despite their unnatural status. (Clearly, the artist’s home is inland, where his imagination is free to create whatever gilled creatures it may.) Close inspection reveals another body near the painting’s margin: a tiny, winged human. Drawn with a light touch, this naked male is nonetheless profoundly sorrowful; his wings allude to human potential and exalted freedom, but his spindly form with head falling to one side is pathetic. All around him is procreative bliss, but he is dejected, forlorn, and very much alone. In the midst of orgiastic unions, perhaps he mourns his rejection, all the while knowing the illusory quality of pleasure, or the empty feeling after ejaculation.

Ceramic-inspired markings pattern two snakes in another work. They are twisted around each other to form a wreath, or a lasso. One fanged head juts out like a grinning pet Medusa; the other is engulfed in a gaseous blob of the blood-semen mixture that, here, looks like bubblegum.

Departing somewhat from the underwater environment of the other works, one painting uses indoor images, geometrically arranged. The large canvas is divided into a checkerboard of shapes representing the fragmented quality of a dream. Patchwork pieces are made up of floor tiles and architectural elements such as skylight beams and bridges. In one square, Zhang’s face appears through a beer mug; in another his friend looks back at him through his own mug. A snake’s head lurks in a bottom square, a used condom in another, and on the tiles nearby are the ubiquitous blood-semen smears. The puzzle is a prism of memory, the jumbled pieces of dream sequences that Zhang can’t quite describe coherently. What once made sense in a dreamscape is now confused—it becomes something new in the retelling.

Elsewhere, a large fish swims after a beer mug with a face peering from inside it. Although the scene stems from Zhang’s brush with drowning, the colors are almost serene; Zhang is still afraid of fish—and of anything associated with accidental death in the water—yet his portrayal of fish is not ugly or terrifying. And without any knowledge of Zhang’s fears, the viewer sees the fish and the beer mug adjacent to the canvases of condoms, takes in everything together, and recalls the sexual energy of bars and nightclubs. The juxtapositions imply that inside bars—where we are attracted by people, televisions, lights, shadows, reflective surfaces, music, and drink—all is a showy mirage; yet in such settings, primitive mating rituals take place nightly, linking modern society to our most primitive animal kin and embryonic origins.

If every one of Zhang’s paintings, as he claims, is a glimpse into his dreams about drowning, then it would seem his nightmares have faded over time and produced aesthetic remnants. Yet new demons, universal ones, have popped out of his work while he processed his fears. The underwater trauma that transformed itself into beauty via paint and repetition reinvents itself here with new sociological and psychological overtones. Something new is displacing his original memories, overlaying passion upon experience, and revealing the intersection of childhood and adulthood.

CLICK HERE FOR "A Joyful Time"

Pacific Bridge Contemporary Southeast Asian Art, 95 Linden Street #6, Oakland CA 94607

Tel. (510) 45I - 8840 Fax. (510) 45I - 8806 email. pacificbridge@asianartnow.com

Gallery hours: Tuesday through Saturday 11 am - 6 pm.